☰

☰

This is the page for Lingowa Gona grammar. Also see phonology, dictionary, word derivation, or go back to the main lingowa gona page

We use the gnomic copula "to" (tu) to make simple statements about identity or physical description. This type of sentence has the following structure: [subject] TO [noun/adjective].

kituIma

ki to ima

I am a human

nilitawutumegawu

ni litao to megao

this rock is big

If the subject is indefinite (not a specific individual), this sentence will be understood as a general statement about what is expected to be always or at least typically true for every individual of that category.

talasawutukana

talasao to kana

(all) oceans are typically blue

(if I know that A is an ocean, I can safely assume that A is blue)

InliginatuInkula

inligina to inkola

a tree is always a plant / (all) trees are always plants

(if A is a tree, then by definition A is also a plant)

Usually these are actions that people do by themselves, mostly without affecting others. This type of sentence has the following structure: [subject] [verb].

pisesaminikulmass

pisesa mini kolmas

A small fish is swimming

kimentemm

ki mentem

I am thinking/imagining

Usually these are actions that people do to other things. They directly affect the object of their action. This 'direct object' is marked by the accusative "si" (si). This type of sentence can have different structures based on convenience because putting things at the end allows you to add a relative clause to give more information about it.

1. [verb] [subject/actor] SI [object/patient] -> emp. on object (most common)

2. [subject/actor] SI [object/patient] [verb] -> emp. on verb

3. SI [object/patient] [verb] [subject/actor] -> emp. on subject

pagusskisiakuwa

pagos ki si'akowa

I drink some water

kisiakuwapaguss

ki si'akowa pagos

I drink some water

siakuwapagusski

si'akowa pagos ki

I drink some water

pudesslasiki

podes la si'ki

She causes/commands me to walk

Cognitive verbs are typically intransitive. It's something you experience mostly without directly affecting others. Sometimes, it has a theme: a thing whose idea or concept of it is involved in that thought. This 'theme' is marked by the pertinential "tan" (tann). This type of sentence has the following structure: [subject/experiencer] [verb] TAN [theme].

kimentemmtannImpaguss

ki mentem tan'impagos

I am thinking of food

laakustimmtannAwiya

la akostim tan'awiya

She hears (the sound of) a bird

lalayudammtannnipumawukukusu

lala yodam tan'ni pomao kokoso

They are happy/pleased about this coconut

This preposition can also be used as a complementizer.

kiUlammtannnitetuneginiss

ki olam tan ni tetone ginis

I saw that this house caught on fire

lapunusstannpanaInabiyuss

la ponos tan pana ina biyos

He said that everyone is alive

Noun phrases are typically head-initial, that means you put adjectives after the noun.

tetunemegawu

tetone megao

a big building

If you put two nouns next to each other, like this: [noun 1] [noun 2], that means it's a [noun 1] that is typically associated with [noun 2].

pasmayineya

pasmai neya

baby clothes (a type of clothes made for babies, not necesserily clothes that are owned by a particular baby)

Posessions are marked by the word "ya" (ya) in this structure: [noun] YA [owner]. This indicates a degree of control over something, e.g. rights to use an object and autonomy over one's body.

pasmayiyaki

pasmai ya ki

clothes which are owned by me

You can make relative clauses using the word "pa" (pa).

Imapasipisesapalmuss

ima pa si'pisesa palmos

the person who caught a fish

pisesapapalmussIma

pisesa pa palmos ima

the fish that a person caught

ImapaUlammtannnesiya

ima pa olam tan'nesiya

the person who saw an island

nesiyapaInaUlamm

nesiya pa ina olam

the island that a person saw

However, numbers and demonstratives goes before the noun.

nayilituyi

nai litoi

not a rock (something which is not a rock, a non-rock)

nilalituyi

nila litoi

zero rocks (no rocks, doesn't imply that something else is there)

duwalituyi

dowa litoi

two rocks

nilituyi

ni litoi

this rock (this thing which is a rock)

niduwalituyi

ni dowa litoi

these two rocks (these things which are two rocks, there are two in total)

duwanilituyi

dowa ni litoi

two of these rocks (there are several rocks, but I only want two)

alulituyi

alo litoi

the other rock (not this one, the other thing that is also a rock)

aluduwalituyi

alo dowa litoi

the other two rocks (there are two rocks aside from this one)

duwaalulituyi

dowa alo litoi

two additional rocks (there are many other rocks aside from this one, we take two of them)

You can make a negative statement using the word "nai" (nayi). It negates the word after it, like this: NAI [word] which means 'not [word]'.

nitunayipisesayi

ni to nai pisesai

This is not a stingray

nayibatesskisipu

nai bates ki si'po

I did not hit you

Open-ended questions are made by putting the word "we" (we) in the place of the missing information.

nituwe

ni to we?

What is this?

pagusspusiwe

pagos po si'we?

What did you eat?

You can also limit the amount of possible answers that you want to receive.

pagusspusiwepadellpisesawatawalawu

pagos po si'we pa del pisesa wa tawalao?

Out of the following: fish and cattle, what did you eat? / Did you eat fish or beef?

Yes-no or closed questions are made using the word "wedantan" (wedantann) in front of the sentence.

wedantannpagusspusipumuyi

wedantan pagos po si'pomoi?

Is it true that you ate a fruit? / What is true about (the statement that) you ate a fruit?

If every part of the statement is correct, you can answer with "panadan" (panadann). If there are some mistakes, you can answer "nai panadan" (nayipanadann) and give your own statement to correct it. If every part of the statement is false, you can answer with "niladan" (niladann).

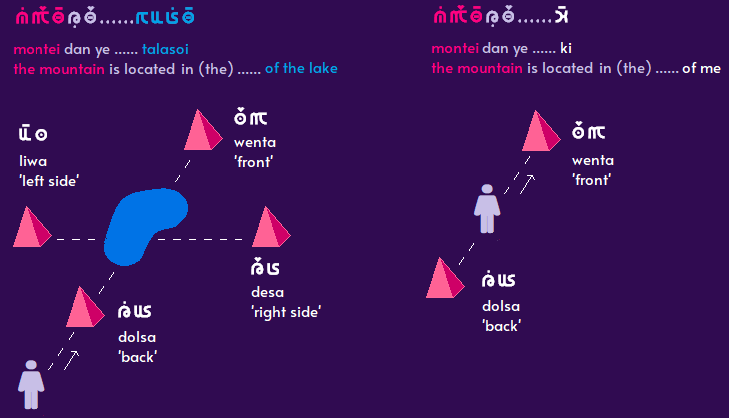

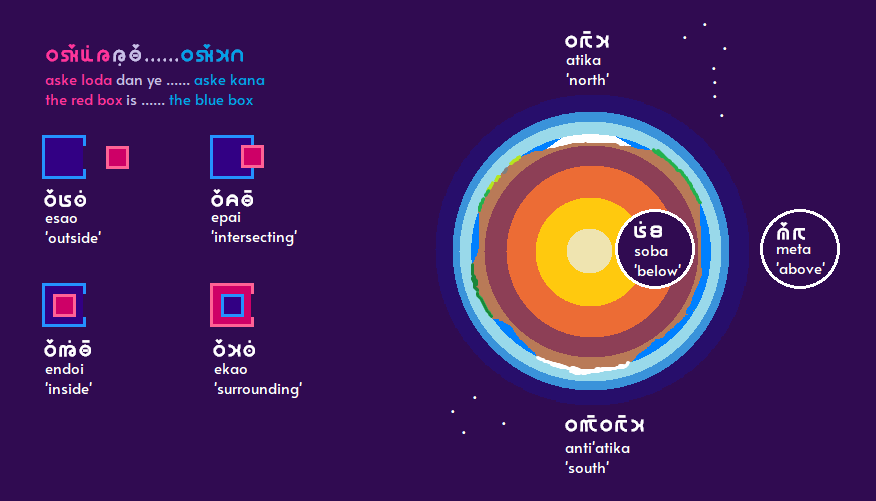

There are four spatial prepositions that indicate thing’s relationship to a place:

You can add spatial nouns after a preposition to further specify its location: [preposition] [spatial noun] [place/location]. Some spatial nouns are oriented to the thing itself; some are oriented to the speaker/observer (left, right, front, back); and some are oriented to Earth.

The locative "ye" (ye) can also function as a relativizer.

kikinesskayetenikasspediyasilituyi

ki kines ka ye tenikas pediya si'litoi

I went to the place where the children were playing with rocks

Words that indicate time are in the form of adverbs and they usually have the suffix “-kal” (kall), for example: “nokakal” (nukakall, at night) and "lomakal" (lumakall, at noon). These words can be placed at the begining or at the end of the sentence. Other concepts, such as duration, beginning, and end are expressed using the spatial prepositions: the vialis “diya” (diya), the ablative “del" (dell), and the lative “ka” (ka) respectively.

nukakalllapudess

nokakal la podes

She walks at night

lapudessdelllumakall

la podes del lomakal

She has been walking since noon

You can also use "kal" as a relativizer.

palmusskisiniawiyakalllanayikulmass

palmos ki si'ni awiya kal la nai kolmas

I caught this bird when it was not flying

You can indicate that an action is finished or completed by adding the prefix "poste" (puste) to the verb. And you can indicate that an action has not started yet by adding the prefix "ante" (ante)

pusteImbesskisiakuwakaInkula

poste'imbes ki si'akowa ka Inkola

I have finished spraying water onto the plants

lumaneyakallkiAntedumemm

lomaneyakal ki antedomem

I have not fallen asleep yet when the morning comes

You can use "poste" and "ante" inside a temporal clause to express events that happen before or after another event.

ImbesskisiakuwakakikalkipusteAnestimm

imbes ki si'akowa ka ki kal ki poste'anestim

I shower myself with water when I have woken up / I take a shower after I wake up

Numbers are placed before the thing they measure, like this: [number] [noun/verb/units]. For nouns, they describe the amount of things. For verbs, they describe the number of repetition.

latiyapunusstannni

la tiya ponos tan'ni

He said it three times

pentasimiyadannyemetaInliginu

penta simiya dan ye meta inligino

There are five monkeys above the tree

niInliginuImetatetametellll

ni inligino to imeta teta meter

This tree is four meters high

Comparatives have set phrases. The positive phrase "more [characteristic] than something" is expressed with the construction: IPEN [characteristic] POSTE [reference] (Ipenn...puste...). Meanwhile, the negative phrase "less [characteristic] than something" is expressed with the construction: IPON [opposite characteristic] ANTE [reference] (Ipunn...ante...).

InliginatuIpennImetapusteki

inligina to ipen imeta poste ki

A tree is tall-er than me / A tree is more tall superior to me

kituIpunnInsubaAnteInligina

ki to ipon insoba ante inligina

I am short-er than a tree / I am less short inferior to a tree

kituIsuImetawapu

ki to iso imeta wa po

I am just as tall as you

In complex comparatives, word order and the placement of reference can help disambiguate which element is being compared.

pagusskisipisesapaIpennpuleyipustetawalawu

pagos ki si'pisesa pa ipen polei poste tawalao

I eat more fish than (I eat) cattle (beef)

(compares the amount of fish that I eat with the amount of cattle that I eat)

sipisesapaIpennpuleyipagusskipustetawalawu

si'pisesa pa ipen polei pagos ki poste tawalao

I eat more fish than a cattle (eats fish)

(compares the amount of fish that I eat with the amount of fish that a particular cattle eats)

Previously, the gnomic "to" (tu) was used in nominal sentences, but it can also be used in verbal sentences to make aphorisms, statements about the general truth or what is typically true.

pisesatubiyussyetalasawu

pisesa to biyos ye talasao

Fishes (typically) live in the sea

(I'm not talking about some particular fish that is alive and exists in the sea. I'm saying that fishes can survive in the sea since it's their natural habitat)

lalatuyudammtannpumawukukusu

lala to yodam tan'pomao kokoso

They (typically) like coconuts

(I'm not talking about that one time when they enjoy a particular coconut. I'm saying that coconuts suit their preferences)

You can also use the gnomic with a temporal clause to make a conditional sentence..

putunayidumemmkallpustepagusspusiakuwakapeya

po to nai domem kal postepagos po si'akowa kapeya

You would not fall asleep if you had drunk coffee

The imperative "so" (su) can be placed before a verb to indicate suggestions, requests, commands, obligations, and needs. It means, "Do this, or else something bad will happen". You can differatiate based on urgency: low ("ipo", Ipu), medium ("mesa", mesa), or high ("ipe", Ipe).

supagusspusiakuwa

so pagos po si'akowa

You should drink some water. (urgency is unspecified)

Ipesupagusspusiakuwa

ipe so pagos po si'akowa

You should really drink some water. (high urgency, e.g. dehydration)

There are also variations to indicate negative imperative "sonai" (sunayi), the lack of any imperative "sowa" (suwa), and conflicting imperative "sowanai" (suwanayi)

pusunayikulmassyeni

po sonai kolmas ye ni

You shouldn't swim here. (something bad will happen if you swim here)

pusuwakulmassyeni

po sowa kolmas ye ni

You are free to or to not swim here. (either way is good)

pusuwanayikulmassyeni

po sowanai kolmas ye ni

You are damned if you swim and damned if you don't swim here. (neither is good)